Stepping Into the Learning Sciences

Not too long ago, probably sometime around summer last year, I first came across the term “Learning Sciences”. In case you’re hearing about it for the very first time right now, what comes to mind for you? What do you envision the field to be about? Hold that thought!

I still remember what I thought back then: Just like with many other disciplines — think Cognitive Neuroscience or Computational Sciences — , the name does not feel entirely telling as to what it’s actually about. Fast forward maybe a year or so, and it just so happens that three weeks from now, I’ll be starting a research internship at ETH Zurich’s Professorship for Learning Sciences and Higher Education (LSE). I only just recently realized this odd sequence of events, and then another thought crossed my mind: Do I feel like I now know what the Learning Sciences are? Well, let’s put it to the test!

The Background of the Learning Sciences

Admittedly, I already somewhat primed you: I mentioned the words “field”, “disciplines”, “research”, “professorship”, and “education”. And you’ve learned things before, obviously. But what do you see before you when you think of learning? University? Music school? Online courses? Documentaries? Workshops? Driving school?

Let’s start with a dry definition and then go from there:

The learning sciences is an interdisciplinary field that studies teaching and learning. Learning scientists study a variety of settings, including not only the formal learning of school classrooms, but also the informal learning that takes place at home, on the job, and among peers. The goal of the learning sciences is to better understand the cognitive and social processes that result in the most effective learning and to use this knowledge to redesign classrooms and other learning environments so that people learn more deeply and more effectively. The sciences of learning include cognitive science, educational psychology, computer science, anthropology, sociology, information sciences, neurosciences, education, design studies, instructional design, and other fields. (Cambridge Handbook of Learning Sciences, p. 37)

Now, as we’d like to make sense of it all, I think you’d agree that textbook definitions are a rather boring and ineffective way of doing so. And we wouldn’t want to be ineffective in learning about effective learning, would we? So, instead, we’ll first go back in time — but not just one year, and not just ten years either. One hundred is more like it!

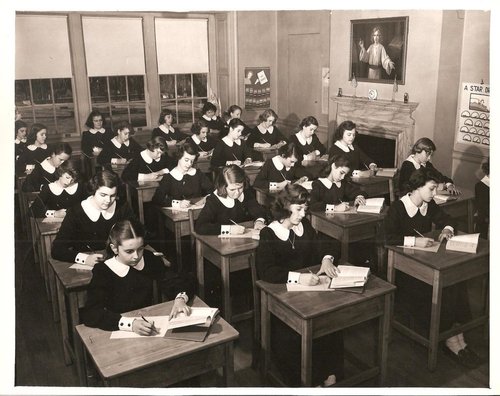

Schools at the beginning of the 20th century followed something called instructionism, and people had little to no idea about how humans actually learn things. If they had ideas, they were nothing more than untested hypotheses — there was no such thing as scientifically investigating various teaching styles, classroom settings or school curricula, let alone how informal learning occurs in places such as museums or libraries.

Unfortunately, instructionism is not just a thing of the past. It is likely that you yourself have experienced it firsthand: It’s a paradigm in which there’s a person with expertise (usually a teacher) whose role it is to pass on the “things” that they are an expert in. These “things” are facts (truths about the world; e.g., “Bern is the capital of Switzerland”) and problem-solving procedures useful to navigating the world (e.g. multiplication and division). According to this framework, students come to school with “empty minds”. These empty minds are to be filled up with said facts and procedures, so that students can go on and perform their later jobs. The more of these facts and procedures a person knows, the more “educated” they are, and how much they know is determined by testing them on their knowledge. The standard curriculum starts out with the easier facts and procedures and then progresses to more complex ones as time goes on. However, what’s considered complex is always up to the experts, not the students —this means that the experts set the order, pace, and content of what is taught.

There is a lot to unpack here regarding why instructionism fails to properly facilitate learning in today’s world— people have written entire books on this. But one very important component is that 21st century jobs require deep conceptual understanding, not just plain “knowledge” of facts and procedures:

Educated graduates need a deep conceptual understanding of complex concepts and the ability to work with them creatively to generate new ideas, new theories, new products, and new knowledge. They need to be able to critically evaluate what they read, to be able to express themselves clearly both verbally and in writing, and to be able to understand scientific and mathematical thinking. They need to learn integrated and usable knowledge, rather than the sets of compartmentalized and decontextualized facts emphasized by instructionism. (Cambridge Handbook of Learning Sciences, p. 38).

A simple example of this, which I’m sure everyone can relate to, are formulas in mathematics. Let’s take the binomial theorem from secondary school algebra: You learn that \((a+b)^2 = a^2+2ab+b^2\) and exam questions will require you to apply this formula. However, in the exam, you are then asked to factor \(z^2+k^2+2kz\) – suddenly the order of the terms is different, the letters are too, and instead of expanding you are now factoring, i.e. “going the other way”. Knowing the fact of the binomial theorem and the procedure of expanding will not be enough, although you may have been encouraged to learn it this way — you’ll also need to understand why and how the theorem is to be modified to fit this novel context. And it is exactly that which requires deep conceptual understanding.

So, how can deep conceptual understanding be taught, or rather, facilitated? This question is not necessarily a novel one. In fact, it brings us to the second half of the 20th century.

How else can learning and teaching be viewed and done?

The following paragraphs will only focus on a few select figures and ideas that were important to the development of the field, more specifically to formal learning (e.g. school contexts). There are many more worth mentioning, but for now, I’d like to focus on just the concept of scaffolding and two researchers named Vygotsky and Piaget:

Lev Vygotsky introduced the very interesting notion of the zone of proximal development (ZPD). The idea behind the ZPD is that there are tasks outside of each student’s “zone” of tasks they can do fully on their own, but that those out-of-reach tasks can be reached with appropriate help. Once the student receives said help, he learns, expands his zone and advances to the next task. “By actively participating in working through these more complex tasks, children learn from the experience and go beyond what they can accomplish alone.” (Cambridge Handbook of Learning Sciences, p. 82)

Scaffolding is another conception of supporting a person’s learning process. You could view it as giving hints or prompts that are just enough for someone to keep making progress towards a goal, but still letting them construct the necessary knowledge to eventually reach it all by themselves. An example of this is a child that can’t tell where the next puzzle piece goes: Instead of showing or telling it where to put the piece, you could instead ask a question such as: “When you look at the shape of that puzzle piece, is there any gap in the puzzle that looks similar to it?”. The child thus still has to make sense of the shape, scan the puzzle, and recognize potential matches all by itself.

Although this technique may seem obvious, and may even be put to use often in parenting, it is not all that common in classrooms. One reason for that may be the usual teacher-student ratio. Fortunately, scaffolding does not necessarily require a physical tutor for each child — it can for example also be done by adding prompts and tips to learning software or book exercises!

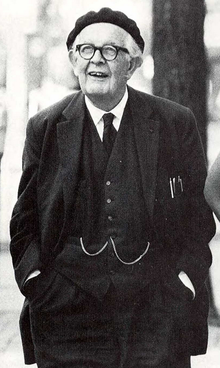

Jean Piaget thought about how children operate, develop and make sense of the world. One of the ideas of his I especially like is that new ideas always emerge from old ones, also implying that children are not an empty vessel to be filled with knowledge, but rather that they come with preconceptions and ideas about the world. For example, there is much research on how infants have an understanding of the basic rules of the physical world, which is of course in direct contradiction to the hypotheses of instructionism. Piaget’s ideas also have many more implications, but instead of going into the nuances and details of all of them, I’d like to end this text by picking up on the one connected question that I feel is most important here:

How can these insights be applied?

First of all, if we had the definitive answer to that, you would probably already know about it, and the world would look very, very different. However, despite the academic field of learning sciences still being in its youth (it is only roughly 30 years old!), it has already produced a good amount of promising ideas which are either already in place or being tested. Here’s a few of them:

- Focusing on improving instructional techniques is not enough — students have to also actively engage in their own learning. Thus, students’ learning processes should also be subject of research, and this demands the use of both quantitative and qualitative research methods

- Students reflecting on their developing knowledge and expressing that in some form is crucial to their learning; this can be done in spoken conversation, written form, illustration, or by creating any kind of artifact

- Facts and procedures are important, but the aim is to make their application to the real world and interrelatedness obvious. The learning environment is essential in achieving this, and project-based learning leverages exactly that: Groups of students start with an unsolved question or problem, share and discuss ideas, draw from scientific practices and apply them to the matter, utilize the technologies available for hints when stuck (scaffolding), share the final solution with the rest of the class, and reflect on the problem-solving process in preparation for the next “run”

- Computers provide a great way of representing abstract knowledge in concrete form, and they also allow for the articulation of developing knowledge as well as sharing and combining of ideas with peers

As the textbook definition at the very beginning mentioned, people working and researching in the learning sciences come from many different backgrounds, ranging from computer science all the way to design studies. But good ideas don’t just come from “learning experts” — I have seen an example of a brilliant educational coloring book developed by a chemical engineering researcher! I’d say the field’s advances are based on the many unique insights that people bring with them, even if it’s just their own experiences with the schooling system. You can have a look at the International Society of Learning Sciences in case you’re interested in looking into the field some more.

I said that this was the final note, but as you probably can tell, what this actually does is open up many more questions about the present and future of learning and teaching, not just in schools but also in informal settings. Even just the book I quoted at various points, the Cambridge Handbook of Learning Sciences, has 800 pages covering many more angles and recommendations.

As I myself learn more about learning (or even learning about learning about learning?), I will continue to cover some of it in writing, much in the spirit of expressing one’s reflection process. So until next time, and thanks for reading!